|

|

Currently there are no events or updates to display. |

Hatching Waterfowl Eggs Basically, there are two ways to hatch waterfowl eggs; naturally and through the use of some sort of incubator. There is more than one type of incubator but today, there is no reason not to use a forced air machine because they are available in the full price range from the most inexpensive styrofoam machines to the most sophisticated cabinet type machines. A forced air machine employs a fan to circulate the air. It means eggs do not have to be cooled as those incubated in still air machines do and that the temperature is more nearly identical in all parts of the incubator.

Even an inexpensive forced air styrofoam incubator can succesfully hatch waterfowl eggs with sufficient attention. Let's go over the basic requirements to hatch waterfowl in a forced air machine: Temperature - 99 3/4 degrees F, moisture requirements - a wet bulb reading of 84 degrees (bantam ducks), 82 degrees (large ducks & geese). The eggs should be turned 90 degrees at least twice per day. Three times is better but much more often is probably unnecessary. The most critical (and most often incorrectly performed) procedures are the turning and the moisture. I gave moisture requirements above for average conditions. It will be necessary to experiment with the conditions in the location in which the incubator is kept to determine what works best. Many experienced waterfowl breeders do not use a hygrometer at all; they go by the size of the air cell in the large end of the egg. By the time the egg is ready to hatch, the air cell should be about 30% of the interior space of the egg - no less than 25%. If the air cell is much smaller, the duckling or gosling will have insufficient room to move around and ream open the egg and the hatch will be poor. If the air cell is too large, the young bird may not be able to reach the shell properly and again, the result will be a poor hatch. It is commonly believed that a great deal of moisture in the incubator will add moisture to the egg; the truth is that one can only slow down the loss of moisture until the hatch is complete. I recommend a separate hatcher which allows the hatching ducklings to be separated according to matings, moisture to be increased, and the eggs left undisturbed until the hatch is complete. It also makes it much easier to keep the incubator clean and sanitized.

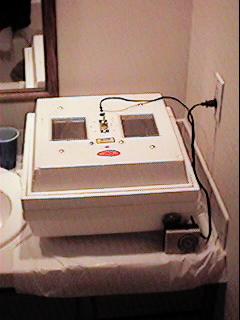

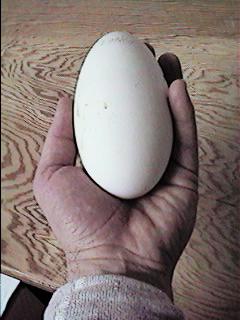

I strongly recommend the hand turning of waterfowl eggs rather than the use of any type of automatic turner. The types of turners which rock the trays work very well for chickens but in my experience do not do the job for waterfowl. How long do waterfowl eggs take to hatch? That depends on the type of eggs one is incubating. Bantam duck eggs usually hatch in 27-28 days for me. The eggs of large ducks and most geese take approximately 28-30 days with Chinas often hatching a day or so earlier. The eggs of Egyptians and Muscovys often take 30-32 days. These are all approximate - eggs are affected by many factors including heat and most incubator thermometers are not 100% accurate. Waterfowl eggs range in size up to the large goose eggs like this one from an older Embden Goose. What type of incubator works best with waterfowl? Almost any type will work in the hands of an experienced and skilled operator who knows how to manipulate the moisture in the specific type of machine. The more control one has over the mechanisms which control moisture and heat, the better chance one has of obtaining good hatches. For that reason, I favor a forced air machine (it has a fan to continuously circulate the air) with a solid state thermostat. The solid state thermostat allows the temperature to be controlled much more precisely than the wafer style of thermostat and is generally less prone to failure. The specific brand of machine which I use myself (Humidaire) also allows the moisture to be manipulated not only by opening and closing the air vents but also by moving the heating bar (which is on a slide mount) closer to or further away from the water pan. In the absence of the ability to move the heat bar, one can add moisture by spraying the eggs when the machine is opened and/or by increasing the surface of the water through use of a larger moisture pan or by putting a sponge in the existing pan. Again, experimentation is necessary.

This cabinet type incubator is what is used exclusively at Acorn Hollow There is so much more to good incubation practices; proper collection and storage of eggs, fumigation of the incubator and little things like staying out of the incubator when a hatch is in progress so that the moisture is not affected. What about natural incubation? For beginners, this is the method most likely to produce good results but it requires regular attention to the needs of the duck, goose, or chicken being used for the incubation. What follows is a brief checklist of things which must be attended to if a successful hatch is to be obtained: 1) Not every type of bird is well suited for natural incubation. Some Calls, for example, have a nasty habit of leaving the eggs about 2/3 of the way through the incubation process. East Indies, on the other hand do very well as setters. Rather than list all those breeds which make good setters, I will list those that in my experience do not. Be aware that individuals in every breed may prove to be an exception. These tend to do poorly as setters: Pekins, Runners and some Calls in the ducks; Chinas among the geese. In chickens, stay away from using Leghorns and other light breeds. As a general rule, older birds make the best setters. Among the chickens, I have had exceptionally good success using Silkies, Wyandottes, and Cochins among the bantam breeds. 2) You must be sure that the bird to which you will entrust your eggs is truly broody (inclined to set on the eggs for the required amount of time.) The bird should have stayed on the nest for two - three days before one can assume that the bird is serious about setting. A bird can be stimulated to become broody by allowing her to accumulate a number of eggs in her nest rather than removing them each day. 3) Do not let a bird set on more eggs than she can cover; if eggs stick out from beneath her, she will gradually chill all of them as she rotates the eggs under her. 4) The bird must be in fairly good physical condition and free from parasites. The bird should be checked for the presence of lice and mites at least weekly during the incubation process. One should also be sure that the bird has a bit of exercise and access to food and water at least once a day. 5) The setter must be provided with privacy and protection from interference of other birds as well as protection from vermin and predators. A dark location is best. 6) If the bird is setting on a wooden floor or if a chicken is being used to incubate waterfowl eggs, added moisture may be in order. This can be done through daily spraying with warm water after the start of the second week of incubation. Again, a check of the size of the air cell as mentioned earlier is necessary. 7) At the end of the first week and again on a weekly basis the eggs should be candled and dead embryos should be removed. It takes some experience to get good at this but it is a necessary skill to learn. Let your nose be your guide, if it smells, throw it out. Exploding eggs will bathe the other eggs in bacteria and will greatly reduce the hatch. 8) You should generally plan to take the ducklings/goslings when they hatch and to brood them separately. In most cases, you can do a better job than the setter unless she is provided suitable quarters to raise the young. Originally published: 10-26-2002Last updated: 03-08-2008 |

Copyright © 1997 - 2025 Acorn Hollow Bantams. All Rights Reserved. | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy